The generation in which I am born into is referred to as the ‘born frees’. We are called this because prior to 1994 South Africa was under a white Afrikaner apartheid rule, wherein black people didn’t enjoy certain privileges and access as compared to whites. Everyone born post-1994 is unfairly labelled a ‘born free’ by those who lived during that dark era.

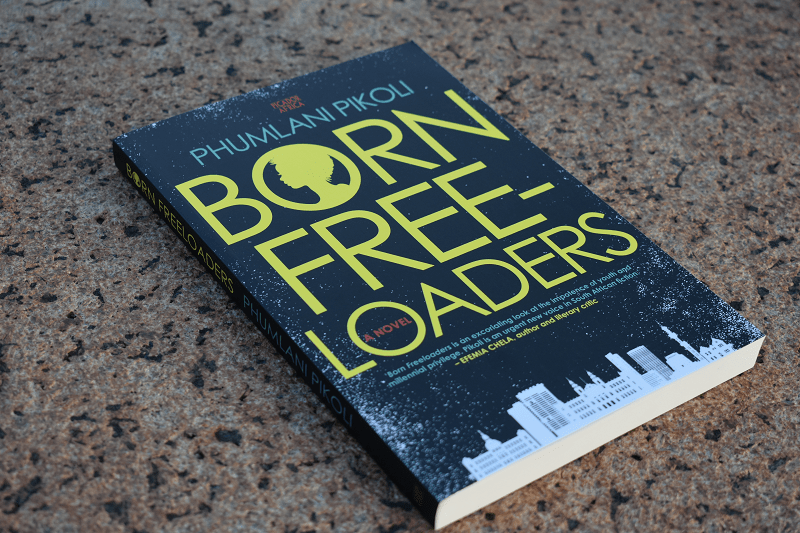

I refuse to believe that we are ‘born frees’, and as I paged through Phumlani Pikoli’s latest offering titled Born Freeloaders, I was hoping he will explain in detail what kind of freedom do the post-1994 young adults enjoy today. Is it political freedom, the right to be able to vote in every election year, social freedom, the right to live anywhere and socialise with whomever or is it economic freedom?

However, I was disappointed with the scribe’s failure to really explain in detail the misnomers attached to this term. The book narrates a story of a modern black South African family living in Pretoria, where the children Nthabiseng and Xolani navigate their way through life.

The front cover of the book paints an image that you’d be reading about ‘born frees’, and I had a different expectation of the book.

In all honesty, in as much as the book tells the story of modern black life in a democratic South Africa, the lifestyles of young people, drinking and partying which consume the lives of the youth in our generation, I couldn’t resonate with the book.

I read it with hopes that as I peruse through the pages, I will find something about a detailed and deeper analysis about the freedom the so-called ‘born free’ generation are enjoying in the democratic dispensation. I feel as though this book was a perfect opportunity to write about the socio-economic challenges that the so-called ‘born free’ generation go through in today’s society.

I agree with Efemia Chela when she said that Pikoli is a new voice in South Africa’s fiction writing because indeed he is a talented writer. However, in this book he dropped the ball on tackling a term that continues to be attached to a generation that is yet to taste the fruits of ‘freedom’ in the 26 years of the country’s negotiated democracy. The youth, mainly those who are born post-1994, are still fighting to have free fee decolonized higher education even under the new dispensation as we have seen in social movements such as the #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall.

If reading fiction is your cup of tea then you would certainly enjoy reading this book. If not, then this book will definitely not resonate with you.

The opportunity to read such a book written by a young author like Pikoli provides one with an opportunity to understand how other young people born in privileged black households view challenges faced by many poor young people across the country.

This is a good story to read if you would like to be entertained and have a well-painted picture of the lives of young modern people living in Pretoria.